Third Party Subpoenas

Discovery can be expensive and burdensome for the parties to a litigation. But it can also be expensive and burdensome to others who aren’t even in the lawsuit, too. This is because American lawsuits allow litigants to take discovery from basically anyone who has relevant, non-privileged information by serving subpoenas on them.

Why should you read this post about third party subpoenas?

Someone wants to take your deposition even though you're not in their lawsuit.

You want to sue someone but some random has the evidence you need to win.

You saw the word “party” and thought that maybe this post could be fun.

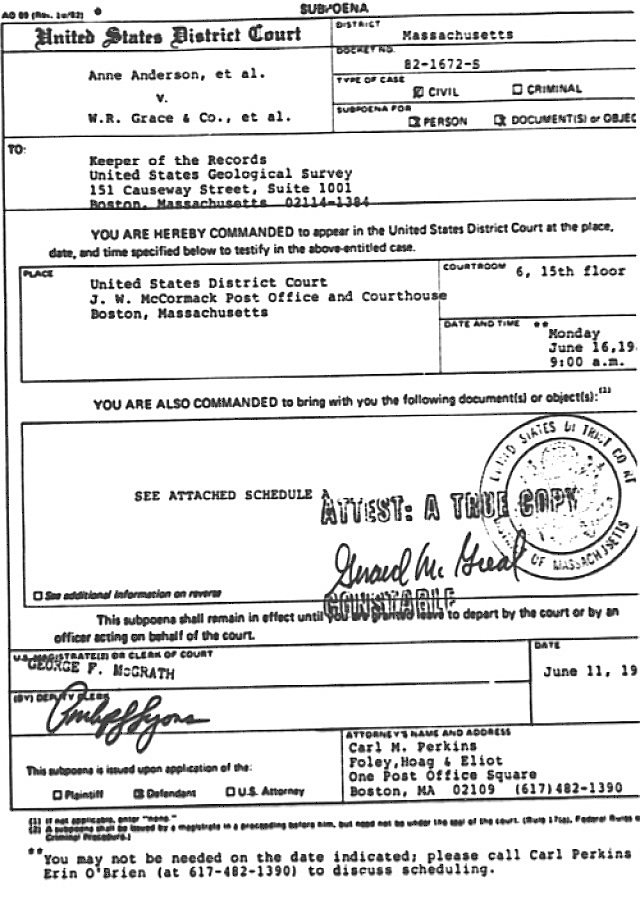

Image credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subpoena#/media/File:Subpoena_usgs.jpg

What Can a Subpoena Do

What is a subpoena? It may sound scary; police officers on Law and Order frequently threatened people with subpoenas and that scared them to voluntarily spill information. But subpoenas are really just discovery requests directed to someone who is not a party to a lawsuit.

Civil procedure rules govern what subpoenas do and how they work. In federal court, Rule 45 governs them. In New York State court, CPLR 3016(b) and 3120 govern subpoenas.

Just like a summons, a subpoena requires a recipient to respond. Whereas a party to a lawsuit is already required to respond to discovery requests, or be subject to an adverse ruling by the judge, a subpoena is a command to a non-party to respond or face some legal sanction.

The two most common types of subpoenas are those that seek documents (a document subpoena, also called a subpoena duces tecum) and those that seek testimony (also called a subpoena ad testificandum). Lawyers may use the latter kind of subpoena, both to get a witness to testify at a deposition and to get a witness to appear at trial and testify on the witness stand.

Preparing and Serving a Subpoena

Lawyers do not need to go to court to ask permission to serve a subpoena. In many situations, they can just issue one themselves. When there is not a pending litigation in the defendant’s jurisdiction, however, they may need to ask the court’s permission.

There are standard forms that lawyers use to prepare a subpoena. For federal court, witnesses use this common form for document subpoenas and this common form for witness testimony subpoenas. It is not uncommon for lawyers to use one subpoena to obtain both kinds of evidence.

Although the form requires the serving party to write out all of the documents it seeks, lawyers often write “See Exhibit A” in that part of the form and then attach a document that lists all of the different categories of documents they seek.

After preparing the subpoena, a party needs to serve the subpoena in the same manner that it serves a summons. Often lawyers reach out to the lawyer for the subpoena recipient, who agrees to accept service without the need for the technical service procedure. The serving party usually also needs to serve a copy of the subpoena on each of the other parties to the litigation, which may also give them the opportunity to fight it in court.

Objecting to a Subpoena and Compelling Compliance

After one party serves a subpoena, another party or the recipient of the subpoena may object by serving a document with the objections. This may prompt the party who served the subpoena to go to court and move to compel compliance with the subpoena. Or the objecting person may go to court and ask it to “quash” the subpoena. These disputes may take place in the court where the litigation is pending, or in a court that has personal jurisdiction over the subpoena recipient.

Grounds for objecting to a subpoena may be the same as objecting to any discovery request: it may be unduly burdensome, or overbroad, or seek irrelevant or confidential information. But there may be other grounds, such as that it requires a witness to travel too far to testify.