Defamation Claims

Many lawsuits arise from a plaintiff’s complaint that the defendant lied about them. A lie feels wrong and can damage reputations, and so it is natural for the subject of the lie to want to do something about it. Since it is generally not criminally illegal to lie, the civil court system provides a way for people to seek a remedy for the lie. This comes up frequently in commercial disputes, where professional reputations are important and where publishers and tech companies publish statements routinely that could subject themselves to liability. But defamation claims can be more complicated than people may expect.

Why should you read this post about defamation claims?

I called you a bank robber in an earlier post and now you want to sue me.

You followed the Johnny Depp v. Amber Heard trial (and the Dominion lawsuit and the Carrol v. Trump case) and now are interested in defamation litigation.

You want to know whether you can go to court every time people say bad stuff about you.

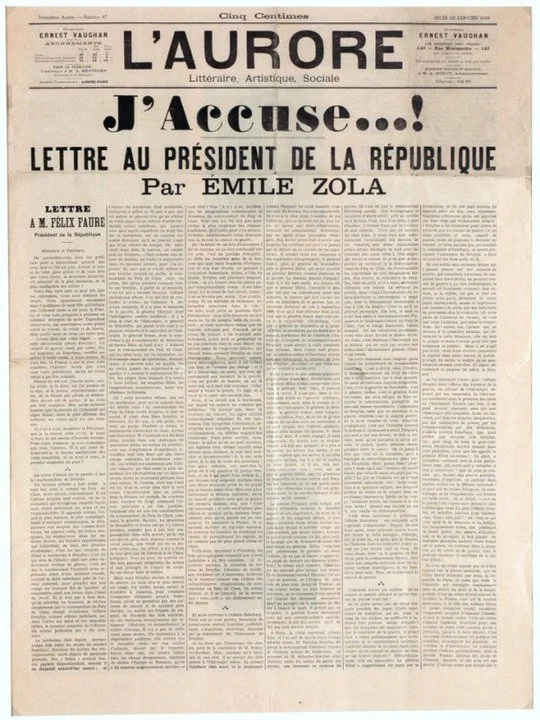

Image credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J'Accuse...!#/media/File:%22J'accuse...!%22,_page_de_couverture_du_journal_l’Aurore,_publiant_la_lettre_d’Emile_Zola_au_Président_de_la_République,_M._Félix_Faure_à_propos_de_l’Affaire_Dreyfus.jpg

Statements of Opinion May Not Be the Basis for a Claim

According to an appeals court, the elements of a defamation claim in New York are: “a false statement, published without privilege or authorization to a third party, constituting fault as judged by, at a minimum, a negligence standard, and, it must either cause special harm or constitute defamation per se.”

The first element requires “a false statement.” This means that opinions cannot be the basis for a defamation claim, since opinions cannot be true or false, even if most people disagree with them. Accordingly, if I call you a bad person, that may not be enough for a defamation claim, even if most people think you are good. But if I said that you cheat on your taxes, that statement can either be true or false, and therefore it could be the basis of a claim if it is false.

There are some grey areas, though. A recent court case held that callings someone a “crook” is too vague to be a specific fact that can be the subject of a defamation claim, even though the plaintiff argued that someone either is a criminal or is not. Questions like this are common in defamation cases.

There Are Different Standards for Public Figures

For the past sixty years, there has been a different standard for public figures in defamation claims. To prevail on many defamation claims, all that may be necessary is to make a false statement about someone that causes damage to them. But since public figures are frequently the source of attention, that makes it difficult to comment about them at all without the risk that some facts are wrong.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in the landmark decision New York Times v. Sullivan, held that the First Amendment protects the freedom to comment on public figures and so only permits defamation claims against them if the defamatory statement was made with “actual malice.” This generally means that the defendant needed to have known that the statement was false when publishing it, thereby only publishing it for the intent of (or reckless disregard for) harming the plaintiff.

A Plaintiff Often Needs to Show Damages

Like most lawsuits, a plaintiff does not just need to show that the defendant did something wrong, but that the wrongful act cost them money. So if I call you a criminal in private and no one hears, it may be hard for you to prevail in a court case since you may not have lost any money because of my lie. But if I published a lie about you in a newspaper or said the lie in a big speech that many people heard, you may be able to show that you lost your job, or became a pariah in society, or other evidence that my lie damaged you.

Some lies, however, do not require evidence of damages. Those lies are called “libel per se,” because the law treats them as so bad as being self-evidently damaging. These are often lies about sexual propriety.

It Is Harder to Domesticate a Defamation Judgment

Someone who wins a lawsuit in another country can often use that judgment to collect money in the United States without re-litigating the merits of the case here. But the law is often skeptical of foreign judgments based on defamation because not every country has the same protections for free speech as the United States. As a result, the law wants to avoid punishing someone for speaking freely in a manner that would be protected here.

In New York, the statute that permits litigants to domesticate a foreign judgment is CPLR Article 53. CPLR 5304(8) states that a defendant can ask the court not to recognize a foreign judgment if “the cause of action resulted in a defamation judgment obtained in a jurisdiction outside the United States, unless the court before which the matter is brought sitting in this state first determines that the defamation law applied in the foreign court's adjudication provided at least as much protection for freedom of speech and press in that case as would be provided by both the United States and New York constitutions.” This statute therefore permits the domestication of the judgment, but only after litigation over whether the foreign law protects free speech as well as domestic law. This may result in some re-litigation of the original issues of the case.

You Can Often Defame Someone in a Lawsuit Without Liability

There are some situations where a defendant can say anything they want and be protected from defamation liability. One such area is in a lawsuit. A normal reaction to being the defendant in a lawsuit is to be appalled that someone wrote complete lies about you in a complaint. Complaints frequently allege that defendants did terrible things, and so defendants often ask their lawyers, “Can I sue the plaintiff for lying about me in a public document?”

The answer is generally no. Statements made in litigation are often subject to a “litigation privilege” that makes them immune from defamation claims. But this immunity is not absolute: many plaintiffs may also comment about their allegations in the press, and those public statements may not have the same immunity.