Actually Arguing

I became a lawyer because, among other reasons, it seemed like the natural extension of high school and college debate clubs. I thought it would be a profession where I would argue and debate for a living. And in TV shows and movies, writers and actors dramatize the work of lawyers by showing them passionately making speeches and arguments for their clients and causes. But rhetorical speechmaking is only a small part of the job.

Many lawyers never work on lawsuits; for example, they may advise clients on tax law or draft complicated contracts. And even as a litigator, my job only sometimes involves actually arguing with someone. And it’s not always in a courtroom.

Why should you read this post about actually arguing?

If you don’t, I will argue with you about why you should.

You’re interested in becoming a litigator, but only because you want more conflict and acrimony in your life.

You like the billions of articles whose theme is “in real life, stuff is less glamorous than people think.”

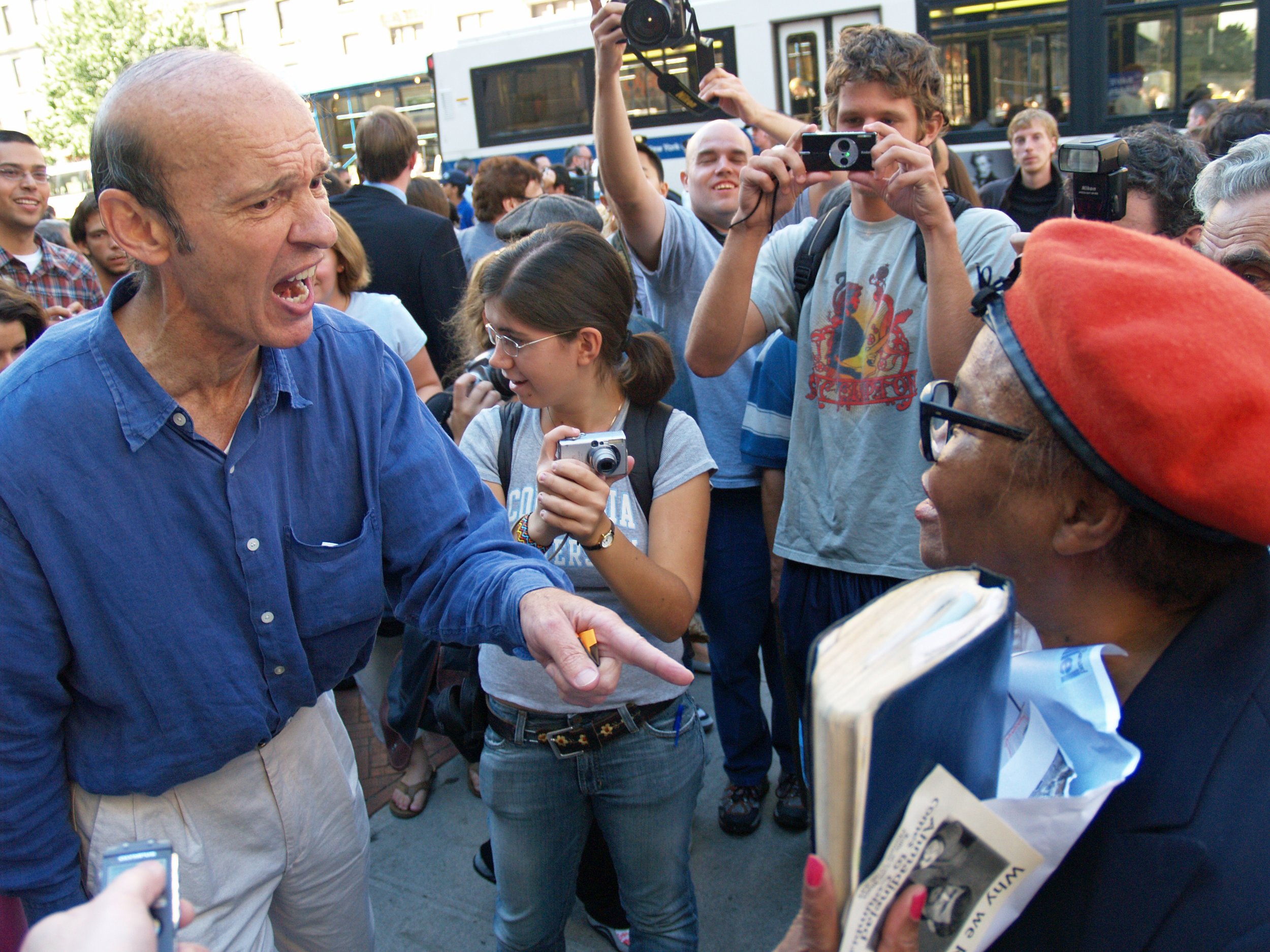

Image credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Screaming#/media/File:Anger_during_a_protest_by_David_Shankbone.jpg

Informal Discussions in the Office

Most of the actual arguments I have take place in my office or on calls with colleagues. It may sound counterintuitive to argue with the people on your own side. But the truth is that arguing back and forth really does refine arguments so that lawyers can discard bad arguments and hone good ones before formally presenting them.

For internal discussions, after researching the law and facts, I may present a possible argument to a colleague. At that point, my colleague may present counter arguments that she may expect a judge or adversary to raise. This will prompt me to adjust my argument or confirm that I have a good response.

Often, before making a formal oral argument, lawyers may rehearse in the office and have a mock debate with colleagues to get ready for the real thing. These are called “moots.”

Additionally, one lawyer on a team may realize that the team is looking at the case the wrong way. This often leads to internal arguments about why a different approach makes more sense.

Arguing With Adversaries

It’s common to have phone calls or meetings with adversaries where each side states their view of the case and responds to opponent’s claims. The purpose of these calls is often to dispose of a case early without substantial litigation, or to settle a case after each side has done some research. It may also be to debate the wording of stipulations or settlement agreements. But often lawyers understand that they will never persuade their opponent that they are wrong. At best, a lawyer can convince her adversary that her position has merits and that further litigation on the subject may not be worth the time and money.

Not every argument with adversaries is about the case itself. Often, arguments are about procedural matters, like scheduling or document disclosures. These arguments may actually persuade an opponent to make a concession or concede a point, though leaving the broader lawsuit unresolved.

Written Briefs Are Where the Real Arguing Is Done

The most dramatic arguments are oral arguments, in court, out loud in front of the judge. But the real arguing is often done in written submissions, filed by the parties with the court. Although these written submissions are not as theatrical as a courtroom argument, they are a better way to make an argument.

First, written submissions require specific legal citations, which a reader can examine carefully and check independently. This way, a reader can confirm that what the author said really is grounded in legal precedent. Although some lawyers cite cases in oral arguments, it is less common and usually less precise. Further, the author of a written brief is forced to make sure that she is accurately stating the law, which she may be tempted to do less precisely when she is speaking aloud.

Second, written submissions can address a wider range of points than someone giving a speech. This is because written speeches don’t get interrupted like oral arguments may and because, generally speaking, authors are permitted more words in a brief than they can say within the time limits of an argument.

Lastly, authors can take their time and craft their written submissions with care. But oral arguments, even well rehearsed ones, may get garbled or come out less precisely than their written counterparts. Similarly, judges and opponents often carefully study a written submission with more depth than they do the transcript of an oral argument.